You are here: home > Spark Plug Q&A > Spark plug construction

Product (85)

- Auto Spark Plug (18)

- Motorcycle Spark Plug (8)

- Chainsaw Spark Plug (6)

- Lawn Mower Spark Plug (5)

- Generator Spark Plug (2)

- Small Engine Spark Plug (3)

- Marine Spark Plug (2)

- Outboard Motor Spark Plug (2)

- Water Pump Spark Plug (1)

- Spark Plug Packing (4)

- Bujia (6)

- Spark Plug Adapter (1)

-

Deep Groove Ball Bearing

(27)

- 6300 Series Bearings (6)

- 6200 Series Bearings (9)

- 6000 Series Bearings (12)

Offers (1)

Spark Plug Q&A (8)

exhibition photos (1)

Service (8)

News (4)

Specially Designed (5)

Blog (19)

Credit Report

Products Index

Company Info

ALEX INDUSTRY LIMITED [China (Mainland)]

Business Type:Manufacturer, Service

City: Ningbo

Province/State: Zhejiang

Country/Region: China (Mainland)

Spark Plug Q&A

Spark plug construction

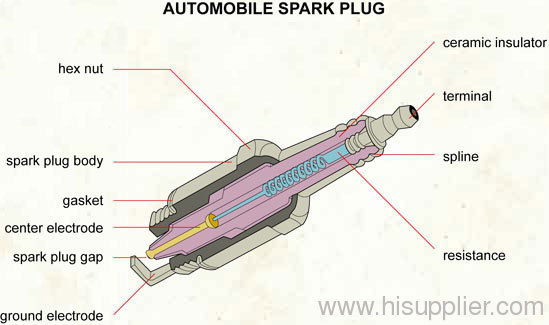

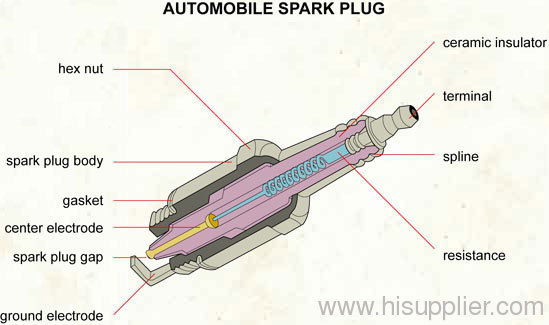

A spark plug is composed of a shell, insulator and the central conductor. It passes through the wall of the combustion chamber and therefore must also seal the combustion chamber against high pressures and temperatures without deteriorating over long periods of time and extended use.

Terminal

The top of the spark plug contains a terminal to connect to the ignition system. The exact terminal construction varies depending on the use of the spark plug. Most passenger car spark plug wires snap onto the terminal of the plug, but some wires have spade connectors which are fastened onto the plug under a nut. Plugs which are used for these applications often have the end of the terminal serve a double purpose as the nut on a thin threaded shaft so that they can be used for either type of connection.

Insulator

Insulator

The main part of the insulator is typically made from sintered alumina, a very hard ceramic material with high dielectric strength, printed with the manufacturer's name and identifying marks, then glazed to improve resistance to surface spark tracking. Its major function is to provide mechanical support and electrical insulation for the central electrode, while also providing an extended spark path for flashover protection. This extended portion, particularly in engines with deeply recessed plugs, helps extend the terminal above the cylinder head so as to make it more readily accessible.

Ribs

Ribs

By lengthening the surface between the high voltage terminal and the grounded metal case of the spark plug, the physical shape of the ribs functions to improve the electrical insulation and prevent electrical energy from leaking along the insulator surface from the terminal to the metal case. The disrupted and longer path makes the electricity encounter more resistance along the surface of the spark plug even in the presence of dirt and moisture.

Insulator tip

Insulator tip

On modern (post 1930's) spark plugs, the tip of the insulator protruding into the combustion chamber is the same sintered aluminium oxide (alumina) ceramic as the upper portion, merely unglazed. It is designed to withstand 650 °C (1,200 °F) and 60,000 volts.

Illustration of compressed mica insulator from 1928.

With the development of leaded petrol in the 1930s, lead deposits on the mica became a problem and reduced the interval between needing to clean the spark plug. Sintered alumina was developed by Siemens in Germany to counteract this. Sintered alumina is a superior material to mica or porcelain because it is a relatively good thermal conductor for a ceramic, it maintains good mechanical strength and (thermal) shock resistance at higher temperatures, and this ability to run hot allows it to be run at "self cleaning" temperatures without rapid degradation. It also allows a simple single piece construction at low cost but high mechanical reliability.

Seals

Seals

Because the spark plug also seals the combustion chamber or the engine when installed, seals are required to ensure there is no leakage from the combustion chamber. The internal seals of modern plugs are made of compressed glass/metal powder, but old style seals were typically made by the use of a multi-layer braze. The external seal is usually a crush washer, but some manufacturers use the cheaper method of a taper interface and simple compression to attempt sealing.

Metal case

Metal case

The metal case (or the "jacket" as many people call it) of the spark plug withstands the torque of tightening the plug, serves to remove heat from the insulator and pass it on to the cylinder head, and acts as the ground for the sparks passing through the central electrode to the side electrode. Spark plug threads are cold rolled to prevent thermal cycle fatigue. Also, a marine spark plug's shell is double-dipped, zinc-chromate coated metal.

Central electrode

Central electrode

Central and lateral electrodes

The central electrode is connected to the terminal through an internal wire and commonly a ceramic series resistance to reduce emission of RF noise from the sparking. The tip can be made of a combination of copper, nickel-iron, chromium, or noble metals. In the late seventies, the development of engines reached a stage where the 'heat range' of conventional spark plugs with solid nickel alloy centre electrodes was unable to cope with their demands. A plug that was 'cold' enough to cope with the demands of high speed driving would not be able to burn off the carbon deposits caused by stop-start urban conditions, and would foul in these conditions, making the engine misfire. Similarly, a plug that was 'hot' enough to run smoothly in town, could melt when called upon to cope with extended high speed running on motorways. The answer to this problem, devised by the spark plug manufacturers, was a centre electrode that carried the heat of combustion away from the tip more effectively than was possible with a solid nickel alloy. Copper was the material chosen for the task and a method for manufacturing the copper-cored centre electrode was created by Floform.

The central electrode is usually the one designed to eject the electrons (the cathode) because it is the hottest (normally) part of the plug; it is easier to emit electrons from a hot surface, because of the same physical laws that increase emissions of vapor from hot surfaces (see thermionic emission). In addition, electrons are emitted where the electrical field strength is greatest; this is from wherever the radius of curvature of the surface is smallest, from a sharp point or edge rather than a flat surface (see corona discharge). It would be easiest to pull electrons from a pointed electrode but a pointed electrode would erode after only a few seconds. Instead, the electrons emit from the sharp edges of the end of the electrode; as these edges erode, the spark becomes weaker and less reliable.

The development of noble metal high temperature electrodes (using metals such as yttrium, iridium, tungsten, or palladium, as well as the relatively high value platinum, silver or gold) allows the use of a smaller center wire, which has sharper edges but will not melt or corrode away. These materials are used because of their high melting points and durability, not because of their electrical conductivity (which is irrelevant in series with the plug resistor or wires). The smaller electrode also absorbs less heat from the spark and initial flame energy. At one point, Firestone marketed plugs with polonium in the tip, under the (questionable) theory that the radioactivity would ionize the air in the gap, easing spark formation.

Side (ground, earth) electrode

Side (ground, earth) electrode

The side electrode is made from high nickel steel and is welded or hot forged to the side of the metal shell. The side electrode also runs very hot, especially on projected nose plugs. Some designs have provided a copper core to this electrode, so as to increase heat conduction. Multiple side electrodes may also be used, so that they don't overlap the central electrode.

Spark plug gap

Spark plug gap

Gap gauge: A disk with sloping edge; the edge is thicker going counter-clockwise, and a spark plug will be hooked along the edge to check the gap.

Spark plugs are typically designed to have a spark gap which can be adjusted by the technician installing the spark plug, by bending the ground electrode slightly. The same plug may be specified for several different engines, requiring a different gap for each. Spark plugs in automobiles generally have a gap between 0.035"–0.070" (0.9–1.8 mm). The gap may require adjustment from the out-of-the-box gap.

A spark plug gap gauge is a disc with a sloping edge, or with round wires of precise diameters, and is used to measure the gap. Use of a feeler gauge with flat blades instead of round wires, as is used on distributor points or valve lash, will give erroneous results, due to the shape of spark plug electrodes. The simplest gauges are a collection of keys of various thicknesses which match the desired gaps and the gap is adjusted until the key fits snugly. With current engine technology, universally incorporating solid state ignition systems and computerized fuel injection, the gaps used are much larger than in the era of carburetors and breaker point distributors, to the extent that spark plug gauges from that era are much too small for measuring the gaps of current cars.

Pre Page:

TIGHTENING TORQUE

Next Page:

What is the difference between B8HS and...